The Tennessee Playbook, Part 1a: Through the Screen Door

Where we're going, we don't need a script

This is the first in a multi-part series looking at Tennessee’s offense under Josh Heupel and what plays the Vols run in various situations.

To kick things off, I thought I’d start at the start and look at how Tennessee opens games offensively. Unlike a lot of teams (I’d guess the majority of teams) Josh Heupel, OC Joey Halzle, and staff do not script a set number of plays to run at the start of a game. Halzle explains:

“We don’t script the first 10, 20 because of the way we play, exactly what you were pointing (out),” Halzle said in response to a question from the crowd. “We’re scripting first and second down, usually. … The ball bounces all over the place with all the different ways we like to spread the field. And you can end up on left hash or right hash like that when you didn’t think there was any chance you would. Someone bounces field and (will) reverse on you…

“If you were trying to script too much, it’s like you were saying — if you give your guys, ‘Hey, these are the first 15 plays,’ and then on Play Two they’re on something different, now you’re messing with them, so they know, like, the first couple thoughts that we want to get to. But they’re also used to adjusting, as well, because, ‘Hey, this is not what we practiced. We’re ready for something new, and here it comes.’”

So Tennessee does not script 15-20 plays like many teams do, and instead script first- and second-down early, looking to adapt based on down, hash, and field position. With that in mind, I thought it would be interesting to look at what plays the Vols are running on 1st and 2nd down on the first two drives of games.

Play No. 1

This probably won’t surprise you if you’ve watched Tennessee football for the last three years, but the most likely play for Tennessee to open a game with is a screen pass. In fact, the screen pass has been 18% of UT’s first 1st downs since 2021, and it’s a pretty good call, too, with a 57% success rate. And that’s just called screens, when you add in RPOs the screens take a 29% share and have an incredible 73% success rate.

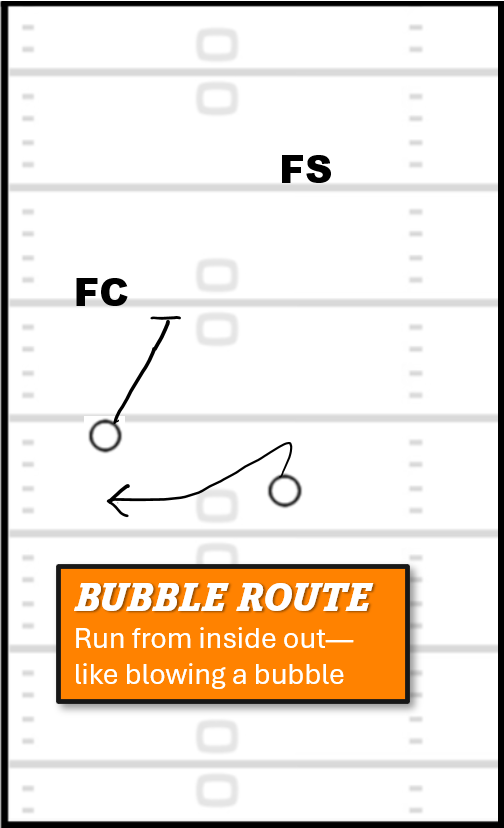

There are many ways to run screen passes, but two of Tennessee’s favorites have been the tunnel screen and the bubble screen. They are very similar, with the main difference being the tunnel is the outside WR running in toward the QB—think of how you’d dig a tunnel, from the outside in—and the bubble has the inside WR running the route to the outside—like blowing a bubble, from the inside out.

You can’t spell tunnel without UT, so we’ll start there. The best example of an opening tunnel screen is from the 2021 Kentucky game, a 75-yard touchdown pass from Hendon Hooker to Javonta Peyton. Here’s the scheme as it was executed on that play. Notice the cross-blocking by the other two WRs to get the best angle on the DBs.

And here’s how it looks in action:

Telling the difference between a called screen and a RPO can be tricky. I believe this is a called screen for a few reasons: a) the TE in motion isn’t helping much in a run situation, b) the linemen aren’t run blocking, and c) Hooker doesn’t seem to be reading a defender, but rather waiting for his target to show.

Compare to this version of the play run against Missouri in 2021 which I believe is an RPO despite some similarities to the Kentucky play. Let’s look at the film first and then the scheme.

There are subtle differences between this play and the UK play. There’s no motioning a second blocker into the scheme for one. And while the OL does end up with a similar cut-block technique, they seem to be paired up in double-teams, as if they were ready to run something like duo. I’m of the opinion that this was a pre-snap read with Hooker recognizing a loaded box and making the call to run the screen.

Another flavor of screen the Vols like to open a game with is the bubble screen, also either from called sets or with an RPO. Here’s an example from the 2022 Missouri game that features a trap blocking scheme that I believe is a called play, not the RPO version. I’ll explain why.

It’s possible this is a RPO. The point of the Y in motion across the play might be to get the Will linebacker to bump out and chase him, effectively blocking the Will and leaving the box light for the trap play. But I don’t think that’s what’s happening here. My opinion is this is a great job of scouting and planning by the UT coaching staff. Watch the play in action, and watch #3, who is assigned to Jacob Warren and who eventually makes the tackle:

That dude was one of Missouri’s leading tacklers in 2022, including seven tackles in this game. But the way #3 pursues on this play, and the way he finishes with the “tackle”, it appears he wants absolutely no smoke. This play has all the earmarks of being designed to attack that player in particular. The trap blocking scheme and play-action hold the linebackers in the box and allow Warren to work against a player that doesn’t seems to be interested in defending. (Outstanding block on the outside by Bru McCoy as well, looking forward to more of that in 2024.)

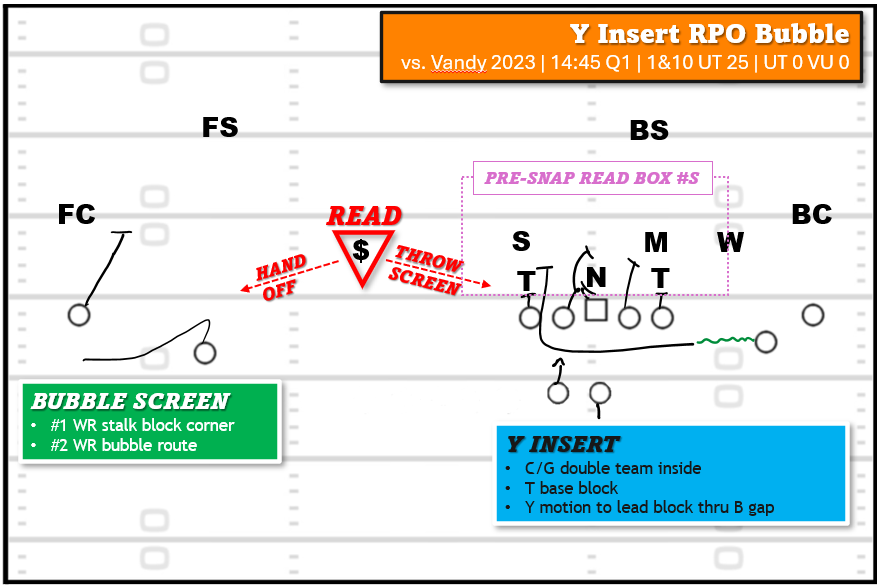

An example of the bubble screen that looks a lot more like a RPO comes from the Vanderbilt game in 2023.

Like the tunnel screen earlier, there is a pre-snap read of the box. As is, it looks like there are six players in the box against six blockers in this Y-Insert scheme from the Vols. That means the player between the box and the slot WR is the conflict defender—if he stays out of the box, then hand off; or if he crashes the box (as he does here), then throw the screen.

This might be a good place to discuss why Tennessee is so fond of screens to open the game in the first place. Obviously the Kentucky play starts the game in the best way possible. But the Mizzou play is probably a ore typical opener. While the play goes for just 7 yards, it is a successful play (gaining 5+ yards on first down), and it has a few other advantages. Tennessee wants to get the ball into playmakers’ hands in space, which the screen does, and they want to run up-tempo, which the screen allows for by being a quick-hitting, high-percentage play. It allows the QB to make an easy early throw and start establishing rhythm. It lets the coaching staff choose which hash to put the ball on, which might be important for subsequent play calls.

As a fan, it’s easy to get caught up in seeing the big, flashy down-field throws that have become regular highlights of the Josh Heupel offense, and feeling a little let down when it’s just another screen pass. But keep in mind, defenses also fear the downfield passing game and might open the game playing a little deeper, allowing more space for a successful screen, and inviting the secondary to play closer to the line, setting up the deep ball later.

I also find it interesting that against some of the better defenses UT has faced the last three years—UGA (x3), Alabama (x3), Clemson, Texas A&M, and Iowa—Tennessee has only used a screen pass as play no. 1 once. I can’t give a definitive answer for why that is. It might be something about how better defenses align that makes the screen less inviting, or it might be an intentional tendency breaker against teams that might have scouted the Vols better. It might also just be a coincidence?

At this point I realize this has turned into more of a clinic on screen passes than I intended at first, so I’m going to let this post stand alone and come back with part B and Tennessee’s other favorite game-opening plays: inside zone and outside power.